The Prayers for the Executioners Fell to Me…

2020 is a year replete with anniversaries and memorial dates. 75 years since the end of the 2nd World War, 100 years since the birth of Pope John Paul II, 30 years since the unification of Germany, 55 years since the Polish bishops wrote to the German hierarchs with a letter saying “We forgive and ask your forgiveness”, 40 years since the launch of the Polish Solidarity Movement.

Our choice of these specific dates is intentional, because it is these dates that were remembered at Auschwitz at the 11th European Seminar Dealing with the Past of Auschwitz Burned by Violence, organized by the German Maximilian Kolbe Foundation and the Centre for Dialogue and Prayer, between 11 and 16 August, 2020. For Auschwitz (Oswiecim, Poland), this year was also an anniversary – 75 years since the liberation of the camp.

The pandemic meant that there were fewer participants than there would otherwise have been: only 11 guests from Germany, Poland, France and Croatia. I was able to represent Russia as a member of the Transfiguration Brotherhood resident in Germany. (The Brotherhood has previously participated in seminars run by the Maximilian Kolbe Foundation in Oswiecim in 2016 and 2017, and in Lvov in 2019.)

Our time there was filled with meetings and events and with meaning and prayer.

Day 1. Auschwitz and Auschwitz-Birkenau

Bright clear blue sky without a single cloud. Hot sunrays light up the entire camp, every barracks, every ruin left of the crematoria and gas chambers that were torn up by the Nazis as they hastily made their retreat. Where many wooden barracks previously stood there are only now foundations, so that the entire area is well visible from one end of the barbed wire barrier to the other. This enormous space was once a one-way destination – a place of death for millions of people. Death made its way past the barbed wire barrier to the outside world, too, as the ashes of those burnt in the crematoria were thrown into the river and onto the surrounding fields as fertilizer.

It was difficult to listen to the words of our tour guide, especially as we could see with our own eyes the proof of everything that went on here. But more shocking than anything are the photographs. Their enlarged copies are on display all across the entire camp area. These were secret photos taken by the Sonderkommando SS: the faces of those condemned to death, Jews, children, and mothers just minutes before going into the gas chamber – two steps away from death. No one told them where they were going or why they were being taken there, but they felt that something unkind was about to happen. The photos show the lost and frightened eyes of people who are condemned and who have been deprived of the right to know that they are about to die.

We shared our impressions that evening.

Christophe Lipert (Erlangen, Germany): “The exactitude with which the Nazis made an account for their prisoners is shocking. Four million people. How is it even possible that people could have done this to each other?!”

Dominic Riedle, Seminarian (Paderborn, Germany): “As a German, it was really important to me to come here. The simple magnitude of what was done here is impossible for the mind to grasp. But even more shocking, if I can express myself in this way, was the “effectiveness” of the destruction.”

David Gospodarek (Poland): “This is the second time that I have visited the memorial site here. I stand here and my mind is unable to comprehend. Maybe this is a psychological defensive reaction. I pray and remember Psalms. How could such a thing happen, as a planned goal, against an entire race and nation?”

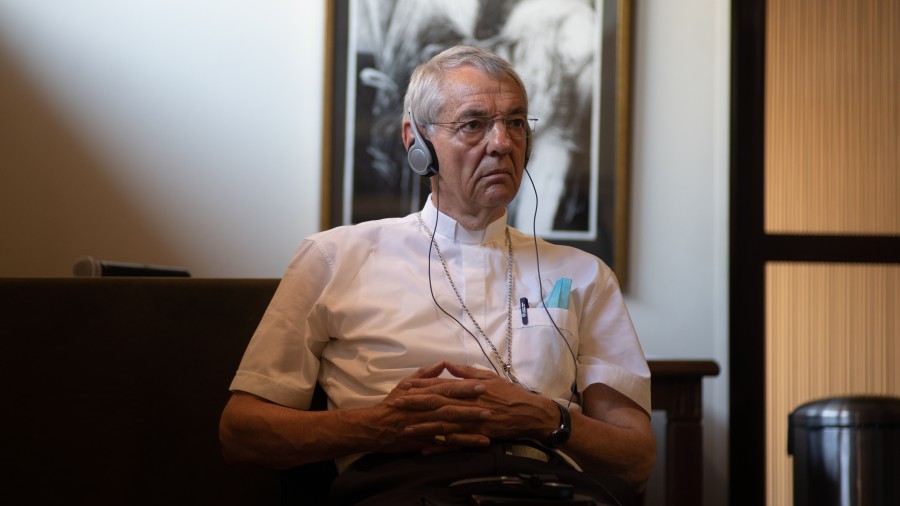

Ludwig Schick, Archbishop of Bamberg (Germany): “I am ashamed. How could people fall so far? How could they render a death machine with such cruel perfection?”

All of us were shocked and amazed by one particular memorial in Auschwitz-Birkenau: it is a wall with photographs of prisoners and of members of their families. People believed and hoped that they would come home. They brought with them photographs of their loved ones and even entire photo albums from their free and happy lives. But all these were taken away and pedantically put into an archive, which is where this wall of memory came from. One can only stand and pray before such a wall, thinking about our families and about whether they are safe from such terror. And to what extent are we safe from the fate of becoming organizers or participants of such violence? This question arose, and we tried to answer it. Archbishop Schick noted that the danger of a repetition of such violence continues – after all, such things have continued in the world after 1945.

Dr. Jörg Lüer, Vice Chairman of the Maximilian Kolbe Foundation: “German idealism died at Auschwitz. The executioners tried to justify themselves to the police by saying “either we do this to them or they would have done it to us.” And their work didn’t stop them from being model fathers and husbands. Auschwitz is now a place of prayerful reflection. Here we come to the understanding that civilization has another dark side. After all, it wasn’t barbarians, but highly educated and even scholarly people who did this evil.”

The photographs of the Sonderkommados SS in which their actions are recorded, speak to the fact that the executioners believed that they were unpunishable and that the world would not learn of their crimes. But the world did find out and desired to fight with evil with an effort of memory and remembrance. For this reason, Auschwitz is open to visitors. For this reason, one of the photo displays in the German Parliament building is from Auschwitz-Birkenau.

Day Two. A Meeting with Auschwitz Survivors

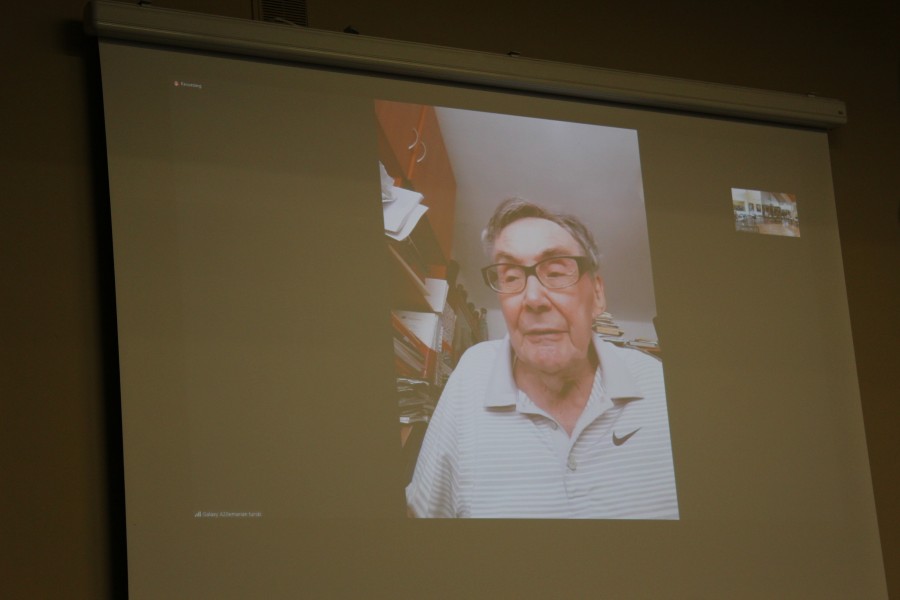

Because of the pandemic, our meeting was via Zoom. Marian Tursky came to Auschwitz on one of the final transports. Previous to this, he lived through two “marches of death” in other camps. Marian is now 94, but he is very lively and has an active lifestyle. His main message to people is don’t be indifferent. Don’t be indifferent to history, to contemporary life, or to changes in the political environment. For this reason, he worked and worked to go to the United States to participate in Martin Luther King’s famous march. And not long ago he wrote to Mark Zuckerberg asking him to react on social media to the lies being spread about the Holocaust. To our question of how he managed to live through Auschwitz, Marian answered that what had helped him was fellowship with other prisoners. They supported each other in getting up every morning, and after a long and tiring work day they made sure that they met to speak with each other, no matter how worn down they were. Friendship, solidarity and fellowship helped them live through hell.

Christina Budnichka (Jewish name Hanne Kuta) – a private guest of the seminar. She was never at the camp itself, but as a child she lived in the Warsaw Ghetto. All of her Jewish relatives perished without even leaving gravesites behind. Kindhearted, responsible people helped her to live, and she will remember these people her whole life. At first, Christina wanted to forget everything, but then she came to understand that forgetting is a false path. It is important to tell people what happened in order to remind them of the importance of love for our neighbours. When she speaks of her profession, she calls herself a storyteller. She meets with many young people from different countries. “In the faces of these people I see my relatives who perished,” she says.

Ludwig Schick’s presentation on the role of the church in remembering the difficulties of the past made a very great impression. In our meetings following our visit to Auschwitz, we spoke of the fact that the Catholic Church had a very inconsequential role in relation to the Nazi regime. With regard to this, the Roman Catholic Church does a great deal to overcome the difficult past. As such, on the 29th of April, 2020, a letter of repentance from the German Bishops was published, which in particular states, “almost no one raised the voice of the Church in Germany in the face of these crimes, or stood up for their neighbours…” In Archbishop Schick’s opinion, it is important to participant in a set of interdependent actions including remembrance of the past, deeds of reconciliation in the present, and leading a life of peace.

Reconciliation is impossible to achieve alone, and is only possible together with someone else. The same is possible to say about reconciliation between God and oneself. Reconciliation doesn’t have an expiration date – it is a long-term commitment. Reconciliation is a step in the direction of truth and toward the Light. He who seeks not reconciliation is walking in an evil direction.

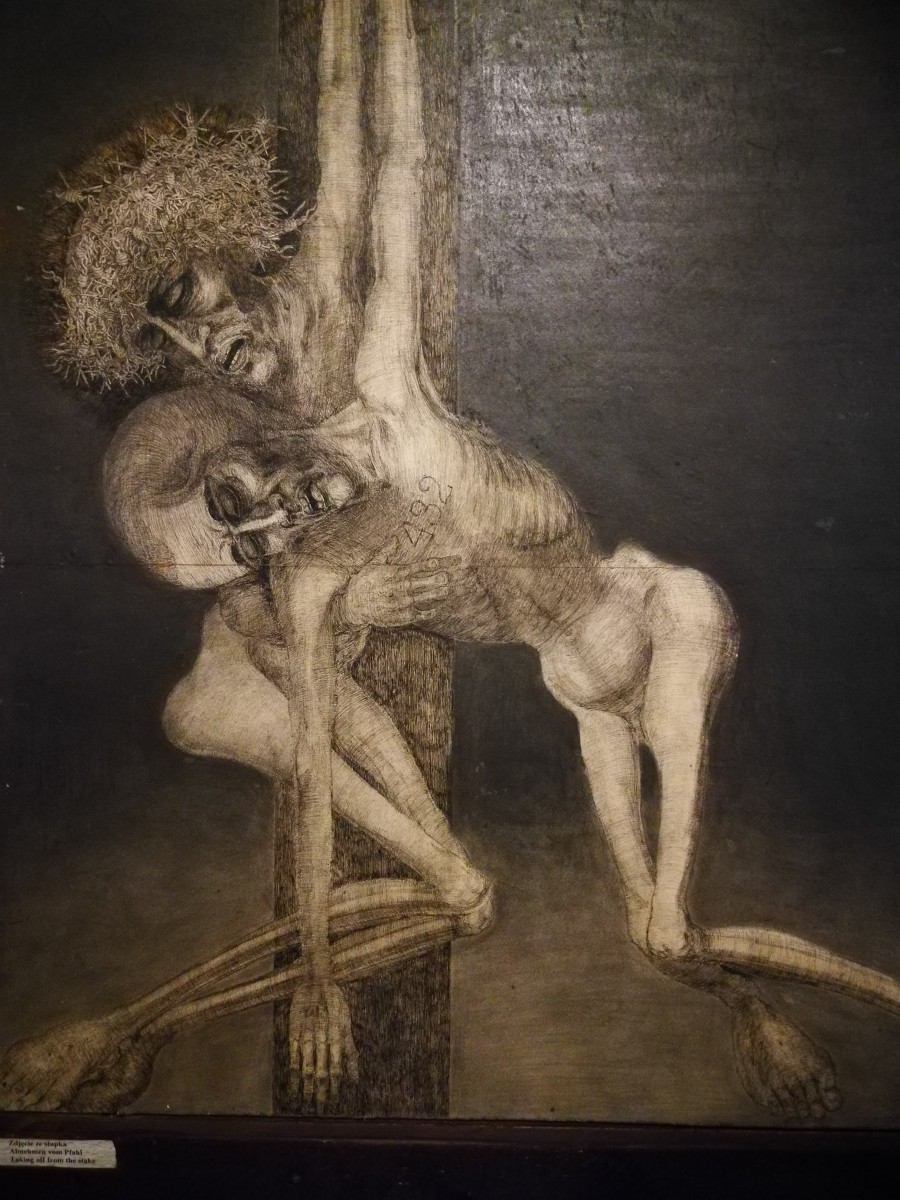

Something memorable, which has become a traditional part of the seminar, is a visit to artist Marian Kołodziej’s exhibition. He himself is an Auschwitz survivor. Father Manfred Dezelers, Head of the Centre for Dialogue and Prayer in Oswiecim, was personally acquainted with the artist. For many years Marian Kołodziej was silent, not letting his memories speak. But with time and thanks to his wife, he once again took up his paint brush in order to honour the memory of those whom he knew personally who have no one else to remember them. He paints his friends along with the numbers by which they were accounted in the camp. Looking at many of the pictures, one has a feeling of apocalypse, like it’s the end of the world. But at the end we are left with hope, that the final enemy, death, will be annihilated.

Day Three. Separating the Victims from the Executioners

One of the common problems about which participants from Germany, Poland and France bore witness, is separating the victim from the executioner when one suddenly becomes the other. This is a topical problem for Poland and France, with which we ourselves are familiar through our “Prayers of Remembrance”, where in a single list of martyrs we read out names of NKVD executioners along with those of their innocent victims.

On the last day of the conference, early in the morning, our group with Fr. Manfred at the head walked along that road – that Way of the Cross – by which the Auschwitz-Birkenau prisoners themselves tread toward their fate. We walked from the gates of the camp to the gas chambers. There are 14 stations, just as with the stations of the cross of our Saviour. At each station, we read a passage from the Gospel, a passage from memoirs of prisoners themselves, and we prayed. Between the stations, we walked in prayer and silence. I was assigned to read at the second station, which is the station at which we pray for the executioners who committed this evil, placed the crosses upon the shoulders of the martyrs, and led their crucifixions. I prayed for their forgiveness before God.

An experience like this is very difficult, nor is it possible for everyone to accept. It brings our Brotherhood together with the Maximilian Kolbe Foundation and with all those who strive to resolve the problems of difficult memories of our past in the Christian way. It is directly associated with faith and with the image of God in man, with the possibility of his resurrection and of transformation, with the desire to listen to and hear our past, our present, and our earth.